Intersectionality

Contents

Intersectionality#

In brief#

Intersectionality focuses on a specific type of bias due to the combination of sensitive factors. An individual might not be discriminated against based on race or based on gender only, but she might be discriminated against because of a combination of both. Black women are particularly prone to this type of discrimination.

More in Detail#

Historically, the topic of intersectionality has been influenced by several studies in the late twentieth century about violence against dark skinned women [4]. On one hand, feminist efforts focused on politicizing experiences of women and on the other hand, antiracist efforts focused on politicizing experiences of people of color. However, both types of activists have frequently proceeded as though the issues and experiences they each detail occur on mutually exclusive terrains. Consequently, this intersectional identity as both women and with dark skin within a discourse targeting to respond to one or the other, women of color are marginalized within both. That is, the intersection of racism and sexism in black women’s lives cannot be captured by looking at the race or gender dimensions separately.

In 2018, the Gender Shades project [1, 2, 5] described the first intersectional evaluation of face recognition systems. Instead of evaluating accuracy by gender or skin type alone, Buolamwini et al.~examined four intersectional subgroups: dark-skinned females, dark-skinned males, light-skinned females, and light-skinned males. The three evaluated commercial gender classifiers, namely, Microsoft Cognitive Services Face [6], IBM Watson Visual Recognition [7], and Face++ (a computer vision company headquartered in China [8]), had the lowest accuracy on dark-skinned females. More precisely, they had the highest error rates for all evaluated gender classifiers ranging from \(20\) to \(35\%\).

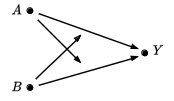

Fig. 26 Interaction Bias, where \(A\) and \(B\) are sensitive variables and \(Y\) is an outcome.#

Studying the problem of discrimination from the lenses of causality, intersectionality can be captured by the concept of interaction [9]. Interaction is observed when two causes of the outcome interact with each other, making the joint effect smaller or greater than the sum of individual effects. Interaction is graphically illustrated in Figure 26, where \(A\) and \(B\) are sensitive attributes and \(Y\) is the outcome1. Note that regular DAGs are not able to express interaction. Figure 26 employs the graphical representation proposed by [10]. The arrows pointing to arrows instead of nodes account for the interaction term.

The interaction term coincides with the portion of the effect due to intersectionality and can be expressed as follows:

\(\textit{Interaction}(A,B) = P(Y_1|a_1, b_1) - P(Y_1|a_0, b_1) - P(Y_1|a_1, b_0) + P(Y_1|a_0, b_0)\)

In practice, intersectionality presents some challenges. The first challenge is related to the complexity of data collection and analysis. In other words, collecting and analyzing data on intersecting factors can be challenging due to limited resources, methodological constraints, and privacy concerns. Second, groups that are not (yet) defined in anti-discrimination law may exist and may need protection [11].

More generally, there are three practical concerns along the machine learning pipeline related to intersectionality in a fairness context [12]. The first problem is related to which factors to consider when training models. It is advised to evaluate the most granular intersecting factors in the dataset while integrating domain knowledge with experiments to understand which are best to include when training models. The second problem concerns the challenge of handling increasingly small groups of individuals. Due to additional ethical considerations, it is advisable to refrain from directly applying conventional machine learning techniques to imbalanced data. Instead, exploring inherent structures among groups with shared identities is encouraged. The third problem is related to evaluating a large number of sub-groups. In the context of binary attributes, fairness assessment often involves comparing group differences using performance metrics derived from the confusion matrix. When dealing with more than two groups, evaluation metrics have a similar structure, albeit more generalized. They are typically expressed in relation to the maximum disparity (or ratio) of a performance metric either between one group and all others [3, 13, 14] or between two specific groups [15, 16]. Hence, methods are proposed for conducting pairwise comparisons more judiciously and introducing supplementary metrics to capture broader algorithmic trends that existing metrics may overlook [12].

Bibliography#

- 1

Joy Adowaa Buolamwini. Gender shades: Intersectional phenotypic and demographic evaluation of face datasets and gender classifiers. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2017.

- 2

Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru. Gender shades: intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. In FAT, volume 81 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 77–91. PMLR, 2018.

- 3

Michael J. Kearns, Seth Neel, Aaron Roth, and Zhiwei Steven Wu. Preventing fairness gerrymandering: auditing and learning for subgroup fairness. In ICML, volume 80 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 2569–2577. PMLR, 2018.

- 4

Kimberle Crenshaw. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stan. L. Rev., 43:1241, 1990.

- 5

Joy Buolamwini, Timnit Gebru, Helen Raynham, Deborah Raji, and Ethan Zuckerman. Gender Shades Project. https://www.media.mit.edu/projects/gender-shades, 2018.

- 6

Microsoft. Face API. https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/ai-services/computer-vision/identity-api-reference.

- 7

IBM. Watson Visual Recognition. https://mediacenter.ibm.com/media/IBM+Watson+Visual+Recognition/0_jbsmp6lq.

- 8

Face++. AI Open Platform. https://www.faceplusplus.com/face-detection/.

- 9

Tyler J VanderWeele and Mirjam J Knol. A tutorial on interaction. Epidemiologic Methods, 3(1):33–72, 2014.

- 10

Clarice R Weinberg. Can dags clarify effect modification? Epidemiology, 18(5):569, 2007.

- 11

Sandra Wachter and Brent Mittelstadt. A right to reasonable inferences: re-thinking data protection law in the age of big data and ai. Colum. Bus. L. Rev., pages 494, 2019.

- 12(1,2)

Angelina Wang, Vikram V. Ramaswamy, and Olga Russakovsky. Towards intersectionality in machine learning: including more identities, handling underrepresentation, and performing evaluation. In FAccT, 336–349. ACM, 2022.

- 13

Wei Guo and Aylin Caliskan. Detecting emergent intersectional biases: contextualized word embeddings contain a distribution of human-like biases. In AIES, 122–133. ACM, 2021.

- 14

Forest Yang, Mouhamadou Cisse, and Oluwasanmi Koyejo. Fairness with overlapping groups; a probabilistic perspective. In NeurIPS. 2020.

- 15

James R. Foulds, Rashidul Islam, Kamrun Naher Keya, and Shimei Pan. An intersectional definition of fairness. In ICDE, 1918–1921. IEEE, 2020.

- 16

Avijit Ghosh, Lea Genuit, and Mary Reagan. Characterizing intersectional group fairness with worst-case comparisons. In AIDBEI, volume 142 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 22–34. PMLR, 2021.

This entry was written by Karima Makhlouf and Sami Zhioua.

- 1

Without loss of generality, all three variables are assumed to be binary with sets of values \(\{a_0,a_1\}\), \(\{b_0,b_1\}\), and \(\{y_0,y_1\}\), respectively.