Safety and Robustness

Contents

Safety and Robustness#

In Brief#

Safety and Robustness: The safety of an AI system refers to the extent the system meets its intended functionality without producing any physical or psychological harm, especially to human beings, and by extension to other material or immaterial elements that may be valuable for humans, including the system itself. Safety must also cover the way and conditions in which the system ceases its operation, and the consequences of stopping. The term robustness emphasises that safety and —conditionally to it— functionality, must be preserved under harsh conditions, including unanticipated errors, exceptional situations, unintended or intended damage, manipulation or catastrophic states.

Abstract#

In this part we will cover the main elements that define the safety and robustness of AI systems. Some of them are common to system safety in general, to software-hardware computer systems or to critical systems engineering, such as software bugs. Some others are magnified in artificial intelligence, such as denial of service, a robustness issue that can appear by inducing an AI system to unrecoverable states or by generating inputs that collapse the system due to high computational demands. Some other issues are more specific to AI systems, such as reward hacking. These new issues appear more clearly in those systems that are specified in non-programmatic or non-explicit ways (e.g., through a utility function to be optimised, through examples, rewards or other implicit ways), as exemplified by systems that operate with solvers or machine learning models. We will pay more attention to these more AI-specific issues because they are less covered in the traditional literature about safety in computer systems. They are also more challenging because of their cognitive character, the ambiguities of human intent, several ethical issues and the relevance of long-term risks. This character and the fast development of the field has also blurred some distinctions between safety (threats without malicious intent) and Security (intentional threats), especially in now popular research areas such as Adversarial Attack and Data Poisoning, and also within data privacy (e.g., information leakage by querying machine learning models or other side channel attacks). In the end, protecting the environment from the system (safety) also requires protecting the system from the environment (Security). Taking into account the changing character of the field, we include a taxonomic organisation of terms in the area of AI safety and robustness and their definition.

Motivation and Background#

Given the increasing capabilities and widespread use of artificial intelligence, there is a growing concern about its risks, as humans are progressively replaced or sidelined from the decision loop of intelligent machines. The technical foundations and assumptions on which traditional safety engineering principles are based are inadequate for systems in which AI algorithms, and in particular Machine Learning (ML) algorithms, are interacting with people and the environment at increasingly higher levels of autonomy. There have been regulatory efforts to limit the use of AI systems in safety-critical or hostile environments, such as health, defense, energy, etc. [1, 2], but the consequences can also be devastating in areas that were not considered high risk, just by the scaling numbers or domino effects of AI systems. On top of the numerous safety challenges posed by present-day AI systems, a forward-looking analysis on more capable future AI systems raises more systemic concerns, such as highly disruptive scenarios in the workplace, the effect on human cognition in the long term and even existential risks.

Guidelines#

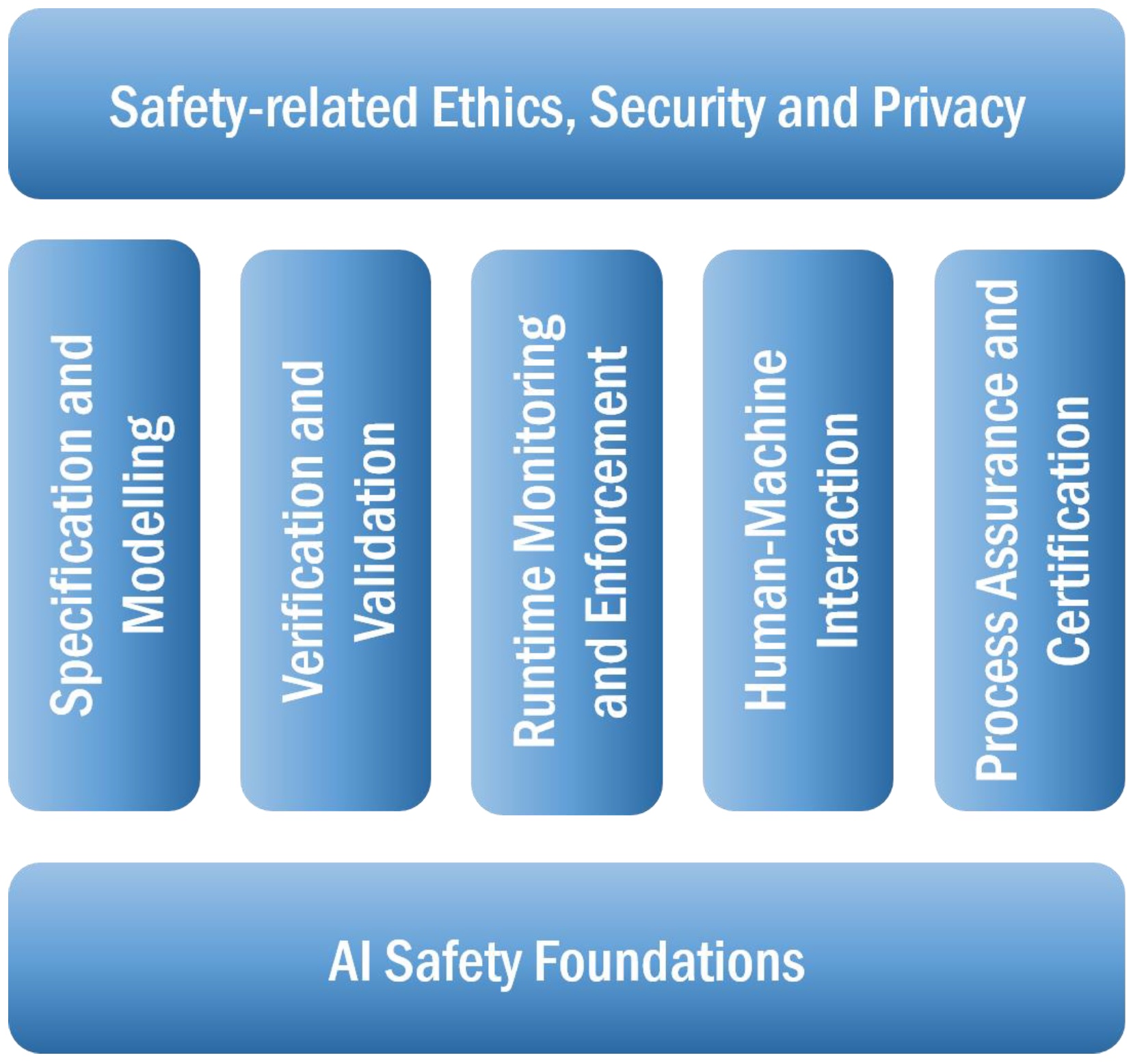

Actions to ensure safety and robustness of AI systems need to take a holistic perspective, encompassing all the elements and stages associated with the conception, design, implementation and maintenance of these systems. We organise the field of AI safety and robustness into seven groups, following similar categorisations1:

AI Safety Foundations: This category covers a number of foundational concepts, characteristics and problems related to AI safety that need special consideration from a theoretical perspective. This includes concepts such as uncertainty, generality or value alignment, as well as characteristics such autonomy levels, safety criticality, types of human-machine and environment-machine interaction. This group intends to collect any cross-category concerns in AI Safety and Robustness.

Specification and Modelling: The main scope of this category is on how to describe needs, designs and actual operating AI systems from different perspectives (technical concerns) and abstraction levels. This includes the specification and modelling of risk management properties (e.g., hazards, failures modes, mitigation measures), as well as safety-related requirements, training, behaviour or quality attributes in AI-based systems.

Verification and Validation: This category concerns design and implementation-time approaches to ensure that an AI-based system meets its requirements (verification) and behaves as expected (validation). The range of techniques covers any formal/mathematical, model-based simulation or testing approach that provides evidence that an AI-based system satisfies its defined (safety) requirements and does not deviate from its intended behaviour and causes unintended consequences, even in extreme and unanticipated situations (robustness).

Runtime Monitoring and Enforcement: The increasing autonomy and learning nature of AI-based systems is particularly challenging for their verification and validation (V&V), due to our inability to collect an epistemologically sufficient quantity of evidence to ensure correctness. Runtime monitoring is useful to cover the gaps of design-time V&V by observing the internal states of a given system and its interactions with external entities, with the aim of determining system behaviour correctness or predicting potential risks. Enforcement deals with runtime mechanisms to self-adapt, optimise or reconfigure system behaviour with the aim of supporting fallback to a safe system state from the (anomalous) current state.

Human-Machine Interaction: As autonomy progressively substitutes cognitive human tasks, some kind of human-machine interaction issues become more critical, such as the loss of situational awareness or overconfidence. Other issues include: collaborative missions that need unambiguous communication to manage self-initiative to start or transfer tasks; safety-critical situations in which earning and maintaining trust is essential at operational phases; or cooperative human-machine decision tasks where understanding machine decisions are crucial to validate safe autonomous actions.

Process Assurance and Certification: Process Assurance is the planned and systematic activities that assure system lifecycle processes conform to its requirements (including safety) and quality procedures. In our context, it covers the management of the different phases of AI-based systems, including training and operational phases, the traceability of data and artefacts, and people. Certification implies a (legal) recognition that a system or process complies with industry standards and regulations to ensure it delivers its intended functions safely. Certification is challenged by the inscrutability of AI-based systems and the inability to ensure functional safety under uncertain and exceptional situations prior to its operation.

Safety-related Ethics, Security and Privacy: While these are quite large fields, we are interested in their intersection and dependencies with safety and robustness. Ethics becomes increasingly important as autonomy (with learning and adaptive abilities) involves the transfer of safety risks, responsibility, and liability, among others. AI-specific security and privacy issues must be considered with regard to its impact on safety and robustness. For example, malicious adversarial attacks can be studied with focus on situations that compromise systems towards a dangerous situation.

Fig. 13 reflects the seven categories described above. Many of the terms and concepts we will expand on correspond to one or more of these categories.

Main Keywords#

Alignment: The goal of AI alignment is to ensure that AI systems are aligned with human intentions and values. This first requires determining the normative question of what values or principles we have and what humans really want, collectively or individually, and second, the technical question of how to imbue AI systems with these values and goals..

Robustness: Robustness is the degree in which an AI system functions1 reliably and accurately under harsh conditions. These conditions may include adversarial intervention, implementer error, or skewed goal-execution by an automated learner (in reinforcement learning applications). The measure of robustness is therefore the strength of a system’s integrity and the soundness of its operation in response to difficult conditions, adversarial attacks, perturbations, data poisoning, and undesirable reinforcement learning behaviour.

Reliability: The objective of reliability is that an AI system behaves exactly as its designers intended and anticipated, over time. A reliable system adheres to the specifications it was programmed to carry out at any time. Reliability is therefore a measure of consistency of operation and can establish confidence in the safety of a system based upon the dependability with which it operationally conforms to its intended functionality.

Evaluation: AI measurement is any activity that estimates attributes as measures— of an AI system or some of its components, abstractly or in particular contexts of operation. These attributes, if well estimated, can be used to explain and predict the behaviour of the system. This can stem from an engineering perspective, trying to understand whether a particular AI system meets the specifications or the intention of their designers, known respectively as verification and validation. Under this perspective, AI measurement is close to computer systems testing (hardware and/or software) and other evaluation procedures in engineering. However, in AI there is an extremely complex adaptive behaviour, and in many cases, with a lack of a written and operational specification. What the systems has to do depends on some constraints and utility functions that have to be optimised, is specified by example (from which the system has to learn a model) or ultimately depends on feedback from the user or the environment (e.g., in the form of rewards).

Negative side effects: Negative side effects are an important safety issue in AI system that considers all possible unintended harm that is caused as a secondary effect of the AI system’s operation. An agent can disrupt or break other systems around, or damage third parties, including humans, or can exhaust resources, or a combination of all this. This usually happens because many things the system should not do are not included in its specification. In the case of AI systems, this is even more poignant as written specifications are usually replaced by an optimisation or loss function, in which it is even more difficult to express these things the system should not do, as they frequently rely on ‘common sense’.

Distributional shift: Once trained, most machine learning systems operate on static models of the world that have been built from historical data which have become fixed in the systems’ parameters. This freezing of the model before it is released ‘into the wild’ makes its accuracy and reliability especially vulnerable to changes in the underlying distribution of data. When the historical data that have crystallised into the trained model’s architecture cease to reflect the population concerned, the model’s mapping function will no longer be able to accurately and reliably transform its inputs into its target output values. These systems can quickly become prone to error in unexpected and harmful ways. In all cases, the system and the operators must remain vigilant to the potentially rapid concept drifts that may occur in the complex, dynamic, and evolving environments in which your AI project will intervene. Remaining aware of these transformations in the data is crucial for safe AI.

Security: The goal of security encompasses the protection of several operational dimensions of an AI system when confronted with possible attacks, trying to take control of the system or having access to design, operational or personal information. A secure system is capable of maintaining the integrity of the information that constitutes it. This includes protecting its architecture from the unauthorised modification or damage of any of its component parts. A secure system also keeps confidential and private information protected even under hostile or adversarial conditions.

Adversarial Attack: An adversarial input is any perturbation of the input features or observations of a system (sometimes imperceptible to both humans and the own system) that makes the system fail or take the system to a dangerous state. A prototypical case of an adversarial situation happens with machine learning models, when an external agent maliciously modify input data –often in imperceptible ways– to induce them into misclassification or incorrect prediction. For instance, by undetectably altering a few pixels on a picture, an adversarial attacker can mislead a model into generating an incorrect output (like identifying a panda as a gibbon or a ‘stop’ sign as a ‘speed limit’ sign) with an extremely high confidence. While a good amount of attention has been paid to the risks that adversarial attacks pose in deep learning applications like computer vision, these kinds of perturbations are also effective across a vast range of machine learning techniques and uses such as spam filtering and malware detection. A different but related type of adversarial attack is called Data Poisoning, but this involves a malicious compromise of data sources (used for training or testing) at the point of collection and pre-processing.

Data Poisoning: Data poisoning occurs when an adversary modifies or manipulates part of the dataset upon which a model will be trained, validated, or tested. By altering a selected subset of training inputs, a poisoning attack can induce a trained AI system into curated misclassification, systemic malfunction, and poor performance. An especially concerning dimension of targeted data poisoning is that an adversary may introduce a ‘backdoor’ into the infected model whereby the trained system functions normally until it processes maliciously selected inputs that trigger error or failure. Data poisoning is possible because data collection and procurement often involves potentially unreliable or questionable sources. When data originates in uncontrollable environments like the internet, social media, or the Internet of Things, many opportunities present themselves to ill-intentioned attackers, who aim to manipulate training examples. Likewise, in third-party data curation processes (such as ‘crowdsourced’ labelling, annotation, and content identification), attackers may simply handcraft malicious inputs.

Bibliography#

- 1

Luciano Floridi. The european legislation on ai: a brief analysis of its philosophical approach. Philosophy & Technology, 34(2):215–222, 2021.

- 2

Michael Veale and Frederik Zuiderveen Borgesius. Demystifying the draft eu artificial intelligence act—analysing the good, the bad, and the unclear elements of the proposed approach. Computer Law Review International, 22(4):97–112, 2021.

- 3(1,2)

Huáscar Espinoza, Han Yu, Xiaowei Huang, Freddy Lecue, José Hernández-Orallo, Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh, and Richard Mallah. Towards an AI safety landscape: an overview. 2019. URL: https://www.ai-safety.org/.

- 4

Dario Amodei, Chris Olah, Jacob Steinhardt, Paul Christiano, John Schulman, and Dan Mané. Concrete problems in AI safety. 2016.

- 5

Iason Gabriel. Artificial intelligence, values, and alignment. Minds and machines, 30(3):411–437, 2020.

- 6

Leslie David. Understanding artificial intelligence ethics and safety. The Alan Turing Institute, 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3240529.

- 7

Stuart Russell, Daniel Dewey, and Max Tegmark. Research priorities for robust and beneficial artificial intelligence. Ai Magazine, 36(4):105–114, 2015.

This entry was readapted from Huáscar Espinoza, Han Yu, Xiaowei Huang, Freddy Lecue, José Hernández-Orallo, Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh, and Richard Mallah. Towards an AI safety landscape: an overview. Artificial Intelligence Safety 2019, https://www.ai-safety.org/. by Jose Hernandez-Orallo, Fernando Martinez-Plumed, Santiago Escobar, and Pablo A. M. Casares.

- 1

FLI’s Landscape of AI Safety and Beneficence Research for research contextualization and in preparation for brainstorming at the Beneficial AI 2017 conference (https://futureoflife.org/landscape/ResearchLandscapeExtended.pdf), the Assuring Autonomy International Programme (AAIP) to develop a Body of Knowledge (BoK) intended, in time, to become a reference source on assurance and regulation of Robotics and Autonomous Systems (RAS), (https://www.york.ac.uk/assuring-autonomy/research/body-of-knowledge/) and Ortega et al (DeepMind) structure of the technical AI safety field (https://medium.com/@deepmindsafetyresearch/building-safe-artificial-intelligence-52f5f75058f1).